On Friday April 22nd, organizers from Filipino groups such as Anakbayan, Migrante and the International Coalition for Human Rights held a silent protest inside the office of the Philippine Consulate General of Toronto, condemning the killings of peasant farmers demanding food relief in the Kidapawan Massacre at the hands of soldiers of the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

Their shirts read “BIGAS HINDI BALA” – “RICE NOT BULLETS”, calling on the Filipino diaspora to pay attention to deaths of two farmers, Enrico Fabligar and Darwin Magyao, as well as the injury, starvation, and detainment of many more, including pregnant women and the elderly. This action was the third in a series of actions that have taken place over the month of April, all with the aim of informing the public about the violent undermining of basic human rights and exploitation of peasants in the Philippines.

The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) had announced as early as September 30, 2015 that a ‘strong’ El Niño would disproportionately affect the Philippines. By January 20th, North Cotabato, a province on the island of Mindanao, had declared a state of calamity under which the Provincial Government is supposed to allocate at least 5% of its internal revenue as calamity funds to be given to those most affected by the drought. The Filipino state gave many declarations but no provisions for the starving farmers. Currently, no funds from the Calamity Fund have reached the farmers.

By the end of March 2016, 40% of the country had experienced the drought; by the end of April, it would be 85%. The Peasant Movement of the Philippines, Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (KMP), which is part of a larger network of organizations known as Bayan, mobilized its chapters in Mindanao to compel the state to address the drought. From March 28th to March 29th, 6,000 farmers and their families from different towns protested near the National Food Authority Office and the Spottswood Methodist Center in Kidapawan City, North Cotabato.

The farmers called upon the government for the release of 15,000 sacks of rice to respond to the drought; the subsidy of rice, seedlings, fertilizers, and pesticides until the drought ends; an increase in farmgate prices of agricultural products; the pullout of military troops in their communities; and the investigation and disbandment of the Bagani paramilitary group being formed by Rep. Nancy Catamco, who are used to terrorize and control the farmers.

Instead of providing them with rice and seedlings, the Philippine National Police and SWAT personnel violently forced the peasants to leave the area by gunning them down, hitting them with batons, throwing stones and blasting them with water cannons from their fire trucks. After the compound was cleared, it was surrounded by some 200 police and the 39th Infantry Battalion of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP).

The drought and violent treatment of farmers is connected to a pattern of reactionary state violence from the Filipino government, who depends on exploiting farmers at home with the aid of rich Western governments. Petronida Cleto, one of the organizers of the protest, connects the treatment of Filipino farmers to those who migrate to countries like Canada: “The system in the Philippines is very export-oriented. They facilitate the movement of people by forcing peasants to sell their possessions to pay multiple fees, forced to sell land to go abroad. And for what? To get Permanent Residency after two years of slavery?!”

Rich Western nations like Canada go to the Third World to extract the resources and labour power of countries like the Philippines. Due to the conditions in their country caused by this resource extraction, Filipino people are forced to leave their homes and families behind in search for work in order to survive. Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program is one way this exploitation takes place because it enables the Canadian State to exploit the labour of Filipino migrants, while at the same time stealing land from peasants, all for its own economic gains.

Organizers aim to raise awareness about the oppressive political climate of the Philippines, where “farmers are not allowed to own their own land, and are killed when they try to stand up and defend it,” said Jesson, one of the main organizers of Friday’s action in Toronto. “This action was about showing that the Filipino community condemns this State-sponsored terrorism and the stealing of land from peasants.”

According to the final report of the National Fact-Finding and Humanitarian Mission (NFHM) of Kidapawan City, it is estimated that 1% of the population in the country own 20% of the total 13.34 million hectares of agricultural lands. Farmers toil day in and day out to produce crops only to have them taken away by huge multinational corporations like Del Monte. They are unable to sustain themselves and are then killed when they ask for what is rightfully theirs to begin with. These are the types of inequalities that the private ownership of land and goods results in, where a small portion of the population profits from the exploitation of the majority who are farmers and peasants.

The state steals and sells the labour of the people to western multinational companies, but the Filipino people do not stand unorganized. The NFHM was conducted within a matter of days after the massacre. Bayan and the KMP mobilizes the peasants based on the fact that they are the farmers of the land. A third of the Philippines’ population is made up of agricultural workers – revolutionary organizations awaken the power of the masses, who already have the skills to maintain their own survival.

When the government watched their people starve, organizations within Bayan like the KMP mobilized 6,000 people to rise and demand that the state open up its stolen resources to the rest of the population. When Gov. Taliño-Mendoza refused to meet the farmers’ demands, offering only three kilos of rice per family once every three months, the peasant leaders unified to reject this offer. The peasants are not asking for charity or handouts; they are demanding the resources they produced from their own land and labour.

Landlords, just like the state, did not miss the opportunity to watch peasants starve. Some have even gone so far as to hoard tonnes of rice in order to drive up prices and increase their profits. The government of the Philippines has done nothing to address this issue, but the New People’s Army (NPA) has taken direct action to reclaim the rice that had been produced by the peasants who are now purposefully being starved by the government and shot at by its army.

The NPA strategically targeted Helen Bernal, who was hoarding more than a tonne of rice. They stormed her warehouse and confiscated 1,384 sacks of rice, along with CCTV monitors, sanding tools, and other electronic equipment in Valencia City, Bukidnon in the country’s southern region. The NPA then redistributed the stolen possessions directly to the places that were most affected by the drought, giving farmers the much needed rice that they had been demanding from the government but were denied, having been served bullets instead.

The deeply organized peasant class, in cities such as Kidapawan and Valencia, along with their comrades in Canada, have the power to hold the corrupt Filipino state accountable. This confrontation clearly shows that organizing and collectivist action is the only way for the peasants to survive and empower themselves during disasters, both “natural” and government-inflicted. The people, when united, will never be defeated. They will only grow stronger.

Photos by Nooria Alam

]]>

On Wednesday March 4, the constituency office of Finance Minister Joe Oliver was picketed as part of the beginning of a nationwide “Campaign Against the 4 Year Limit on Migrant Workers.”

Organised by the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change (MWAC), “a coalition that includes migrant workers, allies, workers’ centres, legal aid clinics, and unions,” protesters denounced a law dubbed the “4-and-4 rule,” which allows temporary foreign workers to stay in Canada for only four years before forcing them to leave for at least another four.

“Our message here is loud and clear: we want the Canadian government to hear our call and remove the 4-and-4 rule,” said Jesson Reyes, an organiser with Migrante Ontario, to the assembled crowd. “Harper, Harper, go away, foreign workers are here to stay!” chanted picketers in response.

“Have you ever lived in a place for four years?” asked Tzazna Miranda, an MWAC activist. “You make friends. You find family. You find a community. You learn your rights, the law. You learn your job.”

“This law doesn’t make any sense,” she continued, “for employers, for workers, or for the economy. It means employers are forced to bring in new labourers every four years, to be retrained at great cost and who know less about their rights. For workers it’s unjust; it’s traumatising.”

The action took place as part of the beginning of the cross-country campaign against the 4-and-4 rule. In the week leading up, protests around the same issue took place in Hamilton, Guelph, Edmonton, Surrey, and the Okanagan Valley. Another rally is being planned for Toronto area residents on March 29.

“When this law comes into effect on April 1, 2015, we will see massive deportations of temporary foreign workers and caregivers across Canada,” Reyes told BASICS in an interview. “We believe that if you are good enough to work here, you’re good enough to stay.”

Many activists have expressed concern that enforcement of the 4-and-4 rule will only lead to a huge increase in undocumented people, as temporary workers may refuse to leave after their visas expire, either because of a lack of opportunities at home or in account of roots they have established in Canada.

The plight of undocumented labourers has gained a great deal of publicity in the United States, where millions work for starvation wages under brutal conditions, and where any attempt to unionise or militate for higher wages or better working conditions leads to crackdowns and deportations.

A similar system has long since begun to be constructed in Canada, with much less fanfare. The municipal government already estimates that up to 500,000 undocumented workers may live in Canada, about half of which probably live in Toronto.

“Almost all migrant workers who live and work in Canada support their families back home,” said Samay Cajas, an organiser from No One Is Illegal. “To lose status and the right to work is devastating for them and their families. To even arrive, many workers incur huge debts.”

Organisers had planned to deliver a person-sized painted STOP sign to the MP. However, the Honourable Mr. Oliver was evidently too embarrassed by the government’s policy to defend it: he refused to meet with protesters and closed his office for the day.

Unlike MPs, however, police officers were present in abundance. During the course of the protest at least four separate squad cars showed up in a parking lot directly across the street from the constituency office. Why the MP for Eglinton-Lawrence regards police as better public representatives of the government than himself remains, unfortunately, unclear.

Police gathering across the street to observe the peaceful protest. A fourth car was stationed about 20 metres to the west.

The March 29 action will take place at Citizenship and Immigration Canada Headquarters, (55 St. Clair E) at 2 p.m.

* * *

For more about the Campaign Against the 4 Year Limit on Migrant Workers, go to no4and4.tumblr.com

]]>Immigrant workers are the first to experience the shift in the labour market towards an increase in temporary work, and the reduction of permanent jobs with benefits and legally enforceable health, safety and labour standards. Many immigrant workers obtain temporary jobs through agencies that are unregulated and fly-by-night. R’s experiences shed light on the difficulties that temporary agency workers in Montreal face, difficulties that create what he described as “a kind of super-stress.”

R came to Canada from Mexico in 2008 and obtained different kinds of jobs through agencies: cleaning trays in a bakery, general cleaning work, jobs clearing snow and ice. When we asked him about safety conditions on the job he said, “Well, the degree of safety that I’ve had is basically nil.” He described “clearing snow at a height of three metres on slippery icy roofs…without safety equipment, cleats, cords, harnesses” for the temporary workers. “At the other end, people that were insured, who worked directly for the company, the whole team was provided with helmets, cleats, harnesses, special tools and special clothing for the cold, and meanwhile all we had was rubber boots.” R left that job but he told us, “One of my buddies fell, fractured his clavicle, and was incapacitated for two or three months.”

R eventually did suffer a serious workplace injury: “The injury that I had was caused by a fall on a production line, on a conveyor belt. We didn’t have access to the controls for the machines, so people had accustomed themselves to jumping the belt. There was no other way, because shutting down the machine would slow things down and cause problems with production. One of the security railings was loose…I fell on my head, and remained unconscious for a few moments. And there, I don’t remember… After what happened, there was no ambulance called. They sent me to the cafeteria. I was in a state of shock. And they continued with the production, which for them was the most important thing.”

The employer took no action whatsoever after this accident. Under pressure to keep working to meet family expenses, and because he didn’t want any trouble, R continued to work. Later, as he continued to get headaches and suffer from tinnitus, he went to see a doctor, but didn’t receive proper care because he hadn’t sought it in time. “I’m still dealing with some gaps, holes in my memory, even to date.”

R told us that he had witnessed other temporary workers sustain terrible injuries on the job: “Well, I remember in one case, there was a station where there were normally supposed to be two people doing packaging, and they only put one person at the station, to try to force her to speed up, but there really should have been two…She slipped and fell and hurt her mouth, opened up her lip. Intense. For another person, it was their hand in one of the conveyor belts, where the trays come out of the oven, got stuck and their skin got ripped off. They had to take them to the emergency room, and the wound was about 10 centimetres long.”

“One of the worst accidents that I saw, a co-worker fell backwards because the floor is always covered in mineral oil, so he slipped and one of the protective railings on the machine that the oil was leaking from wasn’t there, so he fell, lacerated his hand, cutting his tendons and lost the ability to use his hand. Afterwards, this person went to make a demand to the employer, but the employer pointed the finger at him, and then he started to have problems with immigration. I think he was deported.”

Besides the physical dangers, the conditions of work were extremely gruelling. R had to work night shifts, and found changing his sleep rhythm difficult. “It starts to produce a lot of stress in your body, and besides that, physically, you have to be constantly alert and focused on what you’re doing. For example they set you to work in places where normally the machine should be able to function on it’s own, but nobody had calibrated it, because they didn’t bother to contract a technician to do it. It’s controlled with a kind of laser beam in order to keep the size of the loaves of bread standard. But we had to do it manually, so you’re watching these laser beams constantly for an eight our shift… some people ended up dizzy or vomiting. So really, you come out of that totally physically drained.”

But even more draining than the physical stress was the constant psychological pressure that supervisors put on workers. R described this pressure: “They were constantly threatening to fire us…The state of being constantly threatened with dismissal sets off a kind of super-stress, and that can end up also creating psychological problems. I lived through that, and, well, it’s pretty tough. It leaves a mark on you.”

“And the problems then can get transferred through a person to their family, to their wife, their children, neuroses… and a person feels a kind of incompetence towards all kinds of things, their job… being in that kind of situation constantly blocks the kind of consciousness that you need to get out of the vicious cycle. And having a low wage puts you in a situation where, say, you can’t handle having a whole week without work. And as a result, you can’t leave your job. On a psychological level, that’s really hard to deal with.”

As R explained, employers use threats of dismissal to discourage workers from complaining about their working conditions: “Well, even when you invest yourself in doing the job well, doing it right, that doesn’t get noticed and basically they don’t care about you. But say you arrive five minutes late, then they notice, and that’s a horribly serious mistake for one to make. And all of a sudden it’s like you’re on a kind of blacklist. And so it starts to get complicated, because you can’t even make the tiniest of mistakes, and that to is a pretty serious form of pressure. And just as much, it’s a way to keep a worker submissive. I think that’s one of the basics for the use of psychological pressure as a means of controlling workers.”

R elaborated on the fact that temporary workers form a sort of parallel work force in the same place of employment. “In a lot of cases there isn’t even a contract. Obviously we don’t have all of the rights that workers have, we’re basically pawns that they plug in to the assembly line until they’re no good anymore, and then they bring someone else in.”

Even though temp agency workers often do the same job as permanent workers, they are almost always paid less. “I was making nine dollars, in contexts where, in the written contracts that I saw with my own eyes, it was stipulated that a person would be making seventeen dollars an hour, for example, in the packing area. In a context where normally they would have two people working there full time, they have one person, making nine dollars an hour…The difference in pay between what we make and somebody who is hired directly by the company, well, that’s profits for the temp agency.”

Some temporary agencies pay workers irregularly, and frequently, temporary employment agencies ‘disappear’ without paying all of their workers’ wages. As R put it, “Once the term of work is over, sometimes it’s easier for the agency to simply leave its workers behind without paying them at all, without granting them their vacation pay or any other kind of severance, then to go and open up a new agency, and avoid having to even pay taxes to the government.”

R ultimately decided to act on his rights, with the help of organizations that exist to help workers. This involved “going and presenting my complaint and presenting the situations at work, explaining what had happened, and the resulting debts that I had, the fact that I hadn’t gotten my vacation pay, my rights, and also bringing forward other people that were in the same situation, and bringing them right to the Labour Standards Board [in Quebec]. I put in my complaint at Labour Standards, and the person who was my agent looked through the system and found that this agency owed more than a million in income tax. And then they started to follow the agency’s tracks. But the agency had already closed and filed for bankruptcy.”

Eventually, R became a member of the Immigrant Workers Center. He described how this happened: “Well, I contacted the Centre when I was, let’s say I was already at the end of my line… I didn’t have a job anymore, I couldn’t get access to welfare, I had zero income. I had to reach out to organizations that provided assistance. And I met a person who told me about the existence of the Immigrant Workers Center, and told me that they might be able to help. So I got in touch, and little by little they got me oriented, and at every step they accompanied me in filing complaints, they accompanied me with translators, they provided contact with lawyers, through volunteers in the universities, and basically because of that I was able to file my demands the right way.”

R’s message for other workers was: “Well, I hope that many people won’t have to suffer the same kinds of consequences that I suffered for lack of consciousness, lack of knowledge about my rights, also that they realise that this organization exists, that they can get help at any time, even if they’re not dealing with any problems… For people that are going through a problem, the most important thing is to find calm, so that they don’t get immersed in that super-stress, since they do have rights, and those rights can be demanded. They need to reach out, that they need to file letters, they need to make their demands, and not stand there with their arms crossed because if that’s what we do, this situation is going to continue, this abuse of workers…”

Montreal’s Immigrant Workers’ Center has just launched a new newspaper, “La Voix des Migrant(e)s”, from which this article is sourced.

R’s message for the federal and provincial authorities was this: “There are gaps in the law, through which all kinds of agencies can grow and thrive. This is a problem that affects the government itself, because these companies aren’t paying taxes, but also because it damages the image of investment, damages the image of the government. They have to focus their attention on these gaps in the law so that it’s harder for agencies to dodge the law and leave people in situations like this. They should specify exactly who holds the responsibility for paying medical insurance and taking care of workplace safety. Is it the agency, or the company that hires the agency? It needs to be spelled out clearly so that workers can protect their rights.”

]]>

As changes are being considered to the Live-In Caregiver Program that would increase eligibility requirements for participants, decrease the number of applicants accepted, and make it more difficult for participants to obtain permanent residency, it seems timely to reflect on the experiences of caregivers who are presently in the program.

B’s story, gleaned from a face-to-face interview, sheds light on some of the frustrations and challenges that caregivers experience because of restrictions on their mobility, an undervaluing of their prior experience and qualifications, and their vulnerability in their situations of work.

After graduating in the Philippines, B worked as a nurse in the Middle East. She said that she found working as part of a team in the pediatric care and the infectious diseases units at a hospital extremely rewarding. Encouraged by her sister, B decided to come to Canada in 2008, even though this meant giving up a career in nursing. She told herself that she would, after 24 months, be eligible to apply for permanent residence, and be able to find her way back to her original career track. In fact, the wait for permanent residence dragged on, and when we interviewed her, she had been waiting for nine months after submitting her application.

B said her job – which involved caring for two children and doing household chores – had been a good one, relatively speaking. This was because her employers did not require her to live in their home, and respected the hours stipulated in her contract, so she was able to work from 9 to 5. She said that most Filipina caregivers who are part of the LCP work from 6:30 a.m. to 11 p.m. because they are always on call, living as they do at their place of work. She said this was not only exploitative but also terribly stressful and damaging to their health.

While B was not asked to work extra hours, she found that the specific hours she was asked to work were frequently shifted at the last minute: “For me, I always wanted a good working relationship with my employer, so I have to give in most of the time, and it’s really hard.” Also, although she was supposed to work for a single employer, she was expected to work in the households of relatives and friends of her employer: “With the jobs as live-in caregiver, one thing really that I really disagree, but there’s nothing I can do about it, is, like, the employer can just give you to either his friend or their friend, or their parents’, their sister.” She found this difficult as she had to learn the particulars of each household. B said that most live-in caregivers put up with wage-theft, exploitative conditions, and worse, because they tell themselves that after 24 months they will be free to find other jobs. Here again, they are likely to be frustrated, B noted, because the regulations and processing times keep changing. And while they wait, they are not able to take academic courses, as B had hoped to do to requalify as a nurse.

In her time in Montreal, B has appreciated the support of the Filipina women’s organization PINAY, which she says really helps live-in caregivers. She is proud to be a member of PINAY.

]]>By Tascha Shahriari-Parsa

Participants setting up for the Rally on July 27, 2014 to commemorate the anniversary of the Komagatu Maru.

On May 23rd, 1914, the Komagata Maru steamship arrived in Vancouver with 376 passengers who were fleeing India. There were already over 2000 Indians living in Canada, primarily Punjabis, who faced blatant discrimination. Due to racist government policies to keep out the so called ‘brown invasion’, the passengers of the ship were not let off, and the Komagata Maru was forced to return to India by the Canadian government. 20 of the passengers were killed upon arrival by British colonialists’ bullets.

That was the ‘old Canada’. Now, one hundred years later in what we might consider the ‘new Canada’, people of different nations, led by the Indian community, stood together on July 27th, 2014 in Vancouver to commemorate the anniversary of the incident. It wasn’t, however, a passive commemoration. It was not the kind of commemoration that merely acknowledges the barbarity of the past and takes an idle stance on the present. It was not only a day to reflect on the racist government policies of the past, but also a day to connect them with the present. It was a day for marginalized and oppressed communities to voice resistance against the racism that is integral to colonialism and imperialism and the power of oppressive classes today, both in Canada and around the world.

Just over a hundred years ago, the Continuous Passage Act of 1908 was one of the discriminatory laws passed by the Canadian government, a law that required all immigrants to travel to Canada in an uninterrupted journey. The law made it extremely difficult for Asian immigrants to enter Canada, since most trips from Asia involved stops, and actually made it impossible for Indians to enter Canada as immigrants since there were no steamship lines that provided direct service between India and Canada.[1] To combat this blatantly racist law, Baba Gurditt Singh Sandhu led the journey of the Komagata Maru ship to challenge the act.

“Going a little further back in time,” spoke Lakhbir, from the Ghadar Party Centenary Celebrations Committee and the East Indian Defence Committee, “we can see that the economic hard-ships and social desperation that the Punjabi farmers faced due to increased taxation by British Colonialists on farmers forced them to flee the hell of colonial rule to look for better work opportunities. As the British subjects began to arrive in regions like Canada, part of the British Common Wealth, the Immigration laws became more and more discriminatory against the ‘undesirable ones’. The excuse given by the then Government was to avoid conflict between locals and immigrants, because locals feared job loss to immigrants.”

Lakhbir, from the Ghadar Party Centenary Celebrations Committee and the East Indian Defence Committee

Thinking back to this incident, it is important that we do not see it in isolation, but rather understand that racism is and has always been inherent in the settler colonialism on which this country was founded; the appropriation of land and rapid accumulation of capital that once funded the British Empire and now serves the Canadian imperialist ruling class would not be possible without this racism.

If we think back in time to 1492, when Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas, the Europeans immediately began their plans to subjugate the Indigenous people. “They ought to make good and skilled servants…” Columbus writes early on, “With 50 men, you could subject everyone and make them do what you wished,” he said. This was a war of conquest, pursued with racist justifications for the purpose of economic domination. Merely 4 years after Columbus’s arrival in the island of Hispaniola, shared by the modern day Dominican Republic and Haiti, half of the 8 million Indigenous peoples on the island were dead. In the coming decades, this genocide spread through Mexico, Central America, and Peru, killing tens of millions of indigenous people, arguably comprising the most devastating holocaust of history.

The Europeans did not simply arrive in North America for the purposes of settlement – the indigenous peoples were enslaved, forced to work on their own land to grow crops for Europe or extract silver and gold through perilous mines – very similarly to the British occupation of India and the imperialist ventures that continue to exploit the Indian people today. Racism was so vital to this exploitation that it became in and of itself part of the rule of law: racism that has managed to exist independently of economic incentives and racism that has itself governed the nature of society.

Evidently, the refusal of the Komagata Maru very much fits into this legacy of racism. As Lakhbir continued, “On the other hand there were 400,000 immigrants admitted to Canada from Europe in 1913 alone: a figure that remains unsurpassed to this day. One wonders then, if this was really not an act designed as a policy to keep Canada ‘White’? One of the most important reasons was certainly, as we strongly believe, the initiations of National Liberation aspirations and fervour amongst Indian people. The heroic legacy of Indian People in resisting occupation and embarking on the liberation struggle, soon after the occupation was complete, is known to the world. The great Ghadar movement of 1857 is also known as last battle of resistance against occupation and first battle for National liberation. And the 1857 Ghadar rebellion has since inspired, generation after generation of Indian people to wage pitched battles against unjust rule.”

That was the old Canada. What about the new Canada?

As if to make us certain that racism persists today in the policies of our governments, the Federal government of Canada recently passed Bill-C24: The Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act. This is a Bill that is so illegitimate that it violates International Law on Citizenship. Now, the citizenship of a person born in Canada can be revoked if they are thought to be able to claim citizenship in another state through one of their parents – even if that person has absolutely no connection to their parent’s country. What might merit such a revocation? The criteria is membership in “an armed force of a country or as a member of an organized armed group and that country or group was engaged in an armed conflict with Canada” or engagement “in certain actions contrary to the national interest of Canada”.

The wording of this bill is so vague, who knows what could constitute “actions contrary to the national interest of Canada.” What is the national interest of Canada, and who decides it? ; Certainly not the indigenous people whose interests are completely ignored by the colonial government. Rather, the decision is made by the Minister of Immigration and Citizenship, on paper, without a hearing of any sort; The minister merely provides a notice of intent to revoke Citizenship, allows for a letter in response, and then makes a decision. Not only that, but the minister must have only “reasonable grounds to believe” that a person possesses or could possess citizenship to another country in order to deport them – someone who is incorrectly perceived to hold citizenship elsewhere could become stateless, breaching article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Bill C24 has been part of a long line of actions, taken by this government, to persecute the very same people who are fleeing persecution and seeking asylum in Canada. In 2012, the Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act made it so that any group of refugees coming to Canada without papers, by boat or air, could be detained for up to a year without any form of judicial review. The Immigration Minister also brought forth a racist list of 27 nations that he deemed to be ‘safe countries’, making it so that Roma people fleeing persecution from Hungary would have no chance of being accepted as refugees in Canada. In the same year, the conservative government also cut health care for refugees, depriving them from life-saving medication, until the Federal Court struck down the government’s changes in July of 2014.

These racist policies of the Canadian government show that even the thin veil of ‘democracy’ that exists is being taken away – or perhaps its inexistence is becoming clear. People sometimes believe that we have democracy because of the court system, as we have the right to a fair trial and that the rule of law governs over them with justice; but as the capitalist crisis has hit post-recession, the state can’t even afford to put on a facade of democracy anymore. We see this with the stripping away of social programs, the implementation of brutal austerity measures, and bills like C-24.

Thus, while we commemorate the anniversary of the Komagata Maru, it’s important that we do not make the mistake of believing that racist government policies are a mere thing of the past. They have been ingrained in our system since the inception of our settler colonial state and they continue to persist today. The Canadian government has left us with nothing other than what the East Indian Defence Committee considers the “eye-wash politicsof Apologies”: what good are apologies for racist policies of the past when equally racist policies are being enacted in the present?

“Welcome to the new Canada,” said Aiyanas Ormand, a writer for BASICS, on behalf of the International League of People’s Struggle and Red Sparks Union, “Sadly, it is very much like the old Canada that so ruthlessly turned away the Komagata-Maru.”

“We urgently need to build an alliance of oppressed people capable of not only waging powerful defensive battles, but also of linking with the revolutionary movements developing in the global South and of fighting for social transformation here in the belly of the beast,” Aiyanas continued. “We need an alliance of Indigenous peoples, people of oppressed nationalities, and the super-exploited multi-racial working class organized on a firm basis of anti-racism, anti-capitalism, women’s liberation and internationalism.

“The positive Komagata-Maru legacy has been the role of the South Asian community, in Vancouver, leading many very important struggles for social justice, and in linking us here to the great movements of the subcontinent for national and social liberation. Today, we should all commit to carrying on this legacy until this rotten racist patriarchal imperialist system is finally overthrown.”

Therefore, let us stand for the legacy of the ship, and actively fight against racism and all other forms of oppression in the spirit of its passengers.

The Komagata Maru rally was organized by the Ghadar Party Centenary Committee and supported by International League of People’s Struggles, No One is Illegal, Red Sparks Union, and the Revolutionary Student Movement. The following resolutions were also unanimously adapted:

- This rally resolves to dedicate itself to the memory of the Passengers aboard Komagata Maru, who endured ugly unwelcoming gestures upon their arrival in Canada, inhuman conditions while they awaited their fate in the waters of the Burrard Inlet, and death for 20 of them (a miserable life for the rest) on return to India.

- This rally resolves to call upon people to unite and fight against all the anti-people laws, such as Bill C-24, being enacted and enforced to devastate people’s lives. It further calls upon people to stand united and vigilant against the recurrence of Komagata Maru-like incidents.

- This rally believes that, the politics of apologies is nothing more than a corrosive eye wash for people. This rally resolves to denounce the “POLITICS OF APOLOGIES”.

- This rally resolves to denounce the “BILL C-24”, the so called ‘citizen-ship strengthening act’. The rally further resolves to challenge the BILL C-24 and call for its immediate withdrawal.

- This rally resolves to denounce Israel’s occupation of Palestinian Nation, present attack on civilian population in Gaza, killings of innocent women and children. This rally further denounces the WAR CRIMES being committed by Apartheid Israel state. This rally resolves to be in solidarity with Palestinian people’s struggle for freedom.

- This rally resolves to support the Native people’s struggle for their rights.

- This rally resolves to denounce the Fascist Indian state, which crackdown on people’s democratic rights. It further resolves to call for an immediate end to Operation Green Hunt and other such operations. This rally also resolves to Demand for the release of all political prisoners in India.

[1] http://www.whitepinepictures.com/seeds/i/10/sidebar.html

]]>Over 80,000 migrants, including children, have been jailed without charge or trial under the Harper government. Many of these people end up detained in maximum security jails while immigration officials decide whether or not to release them.

It is no wonder then, that undocumented residents in Toronto live under immense stress, faced with the daily fear of being detained or deported.

A new video series on YouTube Confront Injustice: Migrants Know Your Rights that is available in English, French and Spanish, was born out an urgent need for an innovative, proactive response to the distinct struggles faced by undocumented migrants living in Toronto.

“What I found especially troubling was that undocumented folks are the most at risk of incarceration and/or deportation when they attempt to access basic social services such as healthcare, education, shelter and food – support services that every person needs in order to live a life of dignity,” explains Yogi Acharya, the film’s producer. “We hoped to lay the groundwork, for people to be prepared, create a plan, and know the rights they have to protect themselves and their families.”

The video comes at a time when the Harper government is facing widespread public criticism on its changes to immigration policy. Most recently, a federal court upheld that cutting off health care for refugees before their hearings is “cruel and unusual” treatment.

The video complements the ‘Know Your Rights’ guide compiled by the Immigration Legal Committee which outlines strategies and addresses key questions about encounters with police or immigration officials in an accessible format.

Given the shift towards temporariness in immigration over the past 30 years, there are fewer paths to citizenship and increasing insecurity across all forms of status. Estimates of undocumented residents in Toronto currently lie around 200,000 and the recent moratorium on all restaurant workers, and recent changes from Bill C-24 will only add to that number.

“Sadly, precarious and undocumented migrants especially have very limited legal rights, so part of our goal is to capture and communicate those legal realities and how people can safety plan to reduce their vulnerability,” says Karin Baqi, a lawyer and member of No One Is Illegal-Toronto.

However prepared people may be, Acharya admits the real change will come with public pressure, especially from those who can afford to go public on these issues. “As one of the characters in the video says ‘if we actually want to stop immigration from tearing apart our communities, we really need to get together to organize.’ And knowing our limited rights while we do this is one crucial way we can keep ourselves and our families safe.”

To arrange a screening/workshop in your neighbourhood, email us at: [email protected]

An undocumented migrant is pulled over by a police officer while driving. A still from the video Confront Injustice: Migrants Know Your Rights.

Reproduced with permission from author and The Mainlander: Vancouver’s Place for Progressive Politics

AUTHOR’S NOTE | This article emerges from 5 years of working as a community organizer for the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU). Thank you to the VANDU Board for allowing me to lean on their community organizing work and to collaborate in developing an analysis of the ‘mass incarceration agenda.’ And thank you to all the VANDU members who shared their experiences, challenged my ignorance and encouraged me to contribute this analysis to the struggle against the drug war and the war on the poor.

Introduction

The last decade in Canada has seen the strengthening of the instruments of repression of the Canadian State such that we can now begin to describe and analyze the neoliberal containment state as a specific set of policies and institutions. These policies and institutions are aimed at containing the growing social ‘disorder’ and emerging resistance that have resulted from 30 years of the neoliberal economic order.

Far from being a sinister machination of the “Harper agenda,” the neoliberal containment state enjoys a consensus across the ruling class and between electoral parties. No mainstream political party is putting forward a coherent alternative vision for managing monopoly capitalism. The appeals to a softer gentler capitalism coming from the labour bureaucracy and the ‘left’ wing of the NDP have no coherent economic program attached to them. The reality is that the strengthening of the police/incarceration containment state is intimately tied to the social consensus of the bourgeoisie about how to manage capitalism and accumulation in this historical period. The neoliberal containment state is a necessary corollary of the other components of the neoliberal project in Canada:

- Trade liberalization beginning with the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement and NAFTA.

- Privatization of former state enterprises and public services.

- De-funding of redistributive social programs under the cover of austerity and debt reduction.

- Weakening and dismantling of regulatory frameworks including environmental and labour regulations.

- Diminishing the use function of social programs for working class communities and increasing their control function.

It is important to understand the institutions and instruments of this containment state, their connections to the economics of neoliberalism, and their functionality for the Canadian colonial capitalist project as we build movements of struggle, resistance and revolution.

Components of the neoliberal containment state

Legislating criminals

While people often view the components of the neoliberal containment state as purely a product of the Harper government, several important elements were already in place before the conservatives came to power. These include anti-gang legislation and anti-terrorism legislation which interact with and give ideological cover to the broader sweeping criminalization of poor people, drug users, Indigenous people, immigrants and refugees that has emerged in the legislation’s wake.

Under anti-gang legislation, concerns about ‘gang violence’ – stripped of any structural analysis of gangs, where they come from and why people join them – have become a justification for more cops on the streets. In particular urban working class communities of colour and Indigenous communities are targeted by increasingly militarized and violent gang units which exacerbate horizontal violence and effectively criminalize whole communities. As a component of the drug war, these police strategies are much more likely to target and arrest poor low level sellers and users (the low lying fruit) than the big time dealers. Poor people are singled out within what is essentially a criminalized capitalist enterprise with multiple layers of security protecting the upper managers from law enforcement.

Police use gang labeling in much the same way that the imperialist countries use terrorist labeling – to take violence out of its historical and political context and define large groups of people as simply ‘bad guys,’ justifying any level of repression against them.

The terrorism legislation, especially the list of ‘Listed Terrorist Entities’ which includes numerous movements of national liberation and resistance to neo-colonial oppression, has in practice been used as a means to sow fear within immigrant communities, to divide them from their liberation struggles, and to target institutions of Indigenous resistance. The first direct application of the terrorist legislation was against such an institution, the West Coast Warriors Society, in 2006. Since 2001, labeling of Indigenous resistance as an ‘internal terror threat’ has emerged as a normal feature of settler-colonial societies from Canada to New Zealand, Australia and Israel.

We can view these antecedents – anti-gang legislation and anti-terrorist legislation – as the thin edge of the wedge in the initial development of the neoliberal containment state. Main legislative components of the neoliberal containment state have, however, come under the Harper majority government since 2011. They include key pieces of legislation like the so-called ‘Truth in Sentencing Act,’ the ‘Omnibus Crime Bill’ – which includes the dismantling of the Youth Criminal Justice Act leading to harsher sentences for young offenders – and intensified criminalization of immigrants and refugees, including arbitrary and indefinite detention (incarceration) of im/migrants.

The Canadian State has steadily increased the number of people cycling through the criminal justice system, experiencing regular punitive interactions with the police or other disciplinary arms of the State, and facing actual incarceration. This has taken place through a combination of criminalizing economic survival strategies, increasing prison time with mandatory minimum sentences, eliminating ‘double time served’ practices (where sentences are reduced by double the amount of time spent in a remand facility awaiting trial), making pardons and parole more difficult, and closing off legal avenues to status and citizenship for immigrants and refugees.

Mandatory minimums are a major new component in the war on drugs, serving as a mechanism for the criminalization and incarceration of poor people, particularly poor Indigenous people and Black people, in Canada. These provisions impose a minimum sentence for a range of offenses which are mostly linked to the production and distribution of currently illegal drugs. The legislation strips the judge of the ability to exercise discretion, including in cases where it is very clear that jail time will have no rehabilitative benefit and likely no social benefit.

While the rhetoric of mandatory minimums and the ‘tough on crime’ agenda is that these laws target ‘violent offenders’ and people involved in criminal gangs, the reality on the ground is that low level drug sellers – often addicted to the drugs that they are selling and frequently paid in drugs – are the ones who catch the vast majority of charges. Poor and overpoliced neighbourhoods in Canada’s major cities supply most of the ‘candidates’ for incarceration. In a recent case in B.C., where the judge refused to give the one year mandatory minimum, the ‘drug dealer’ is a poor man who is selling to support his own addiction. The mandatory minimum applies because of his previous ‘criminal history’ which includes a previous drug charge.

The legislative component of this containment state has both an ideological function and a control function. Ideologically, the legislation and ‘tough on crime’ discourse exploits and directs the economic insecurity of the middle class and more established working-class:

- Directing the anxiety (and hostility) of the increasingly economically insecure middle class towards ‘downstream’ threats: the ‘disorderly’ poor and unemployed; ‘criminals’; ‘Indians’ and ‘terrorists.’

- Exploiting intraclass divisions between the securely employed working-class and the unemployed working-class; and between working-class people with citizenship and working class people who are temporary foreign workers or migrant workers without status.

The control function also plays on different levels associated with maximizing the rate of exploitation and containing potentially unruly or rebellious populations:

- Physical control and intimidation of the systematically excluded portions of the working-class – workers with addiction; serious physical and mental illness, the elderly, single mothers caring for children and other caregivers with dependents. Physical containment and intimidation supports the slashing of spending on programs that support this group.

- Intimidation of new immigrants, temporary foreign workers and workers without status as a means to maximize the rate of exploitation by the Canadian capitalists who employ them.

- Identification and containment of Indigenous assertion of territorial and self-determination rights.

Strengthening the institutions of repression: Police

Despite the fact that the crime rate (including violent crime) has been falling since 1991, the aggregate expenditure on Canadian police continues to rise, reaching $13.5 billion in 2012. In 2012 there was a slight dip in the number of actual cops on the job (slightly less than 70,000), but this is only because new ‘authorized’ (funded) police positions have not yet been filled. Meanwhile, the trend of increasing numbers of private security guards also continued, with over 140,000 licensed security guards in Canada.

There are also about 7,000 uniformed Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) officers across the country of which more than 3,000 are armed with semi-automatic 9mm Beretta pistols. While most of the CBSA officers are deployed at borders, ports, and airports, a small proportion of these are engaged in internal policing and removal of immigrants, refugees and migrants. They constitute an important added layer of the containment state and of surveillance, harassment and violence in the lives of immigrant, migrant and refugee communities.

The main role of police in the neoliberal containment state is functional, as the enforcers of the criminalizing legislation. However, police also constitute a semi-autonomous interest group advocating ‘tough on crime’ policies to justify increasing budgets and perpetuating the cycle of criminalization through aggressive over-policing of poor neighbourhoods and communities, a practice that has been characterized as ‘mining for crime.’

In 2013, Vancouver Police Department Chief Jim Chu earned $314,000, enough to put him squarely in the 1% along with other top police and RCMP managers. Even the rank and file cops, however, make as much as high level managers in capitalist firms – 650 VPD members make more than $100,000 and 3,000 Toronto cops are in this range. They are very highly paid for a job that is neither particularly dangerous (not in the top ten most dangerous occupations in Canada) nor requiring any particularly specialized skills. Moreover while police do not directly exploit workers, they enjoy a high degree of autonomy, prestige, and exercise a huge amount of ‘delegated’ class power as part of their job. So the material interest and class position of cops tie them profoundly to the ruling order.

Associations of chiefs of police as well as various police associations act as lobby groups for ‘tough on crime’ policies, despite their demonstrable ineffectiveness, exploiting the profoundly ahistorical and ideological construction of police as neutral and disinterested ‘protectors of public safety.’

Strengthening of the institutions of repression: Mass incarceration

Canada is currently undergoing what the National Post described in 2011 as “the largest expansion in prison building since the 1930s.” Some of this expansion is happening in the federal system (about 2,000 spots under construction at the time), but the vast majority of the spots (about 9,000 – some of which have now come online) are in the provincial system. Mostly these are remand spots. Remand is prison for people awaiting trial who have not yet been convicted of the crime for which they are charged. The new Edmonton Remand Centre (pictured below) is an example of this type of facility. It is a 16 hectare maximum security facility built at a cost of $580 million and built to house 1,952 prisoners, with room to expand by almost 1,000.

B.C. is also expanding remand space. The province is spending about $500 million to build new prisons in the Lower Mainland and the interior of the province. The recently completed 216-cell remand centre in Surrey makes the Surrey Pretrial Centre the largest jail in the province. In the interior a new 378 cell remand centre is being built on land owned by the Osoyoos Indian Band. In addition to considerably increasing the overall capacity to lock people up in the province, especially individuals who have yet to go to trial, these new prisons are almost entirely privatized. The staff and administration of the prison are public employees, but every other aspect of the facility is privatized: a contract to build-design and operate the facility (in the case of the Surrey facility this was awarded to Brookfield International, one of the largest and most profitable real-estate management companies in the world); health services; food services; and laundry. So while the profiteering is not as crass as it is in the corporate prisons in the U.S, there is nonetheless considerable profit taking in the neoliberal containment state.

Remand is where poor people being cycled and recycled through the criminal justice system do the vast majority of their time. This includes months awaiting trial, often without having committed any violent crime. Remand facilities are built as short term holding facilities even though they are now where the majority of prison time in Canada is served. They are maximum security, with one or more people locked in a tiny cell for 23 out of every 24 hours. They have no access to educational or self improvement programs, and no pretence at rehabilitation (after all the people in these facilities have not yet been found guilty of a crime). On any given day about 60% of incarcerated people in Canada are in remand.

Conditions in remand are so punitive that some people charged with minor crimes will plead guilty just to speed up the judicial process and get out of remand and into a less punitive prison environment (like a low or medium security facility) or on to some kind of parole. But the conditions of parole are often unreasonable, frequently resulting in rearrest and contributing to the massive numbers of people incarcerated for administration of justice type charges. For highly criminalized populations, the accumulation of convictions makes individuals increasingly vulnerable to re-incarceration. Administration of justice charges (failure to appear in court, breach of a court order, breach of a condition of parole) now constitute the most common charge in Canadian criminal courts (21% of all cases) and 42% of all charges in B.C.

In a 2011 Op Ed for the Toronto Star, Conservative Senator Hugh Segal notes that “less than 10 per cent of Canadians live beneath the poverty line but almost 100 per cent of our prison inmates come from that 10 per cent.” Segal cites the work by Star journalists Sandra Contenta and Jim Rankin whose analysis of a ‘one day snapshot’ of who is in Toronto jails showed that the vast majority of prisoners were drawn from a few very poor neighbourhoods. This is a process – referred to above as ‘mining for crime’– driven by heavy police presence, stop and search practices, and the policing of so-called street disorder. In these neighbourhoods the police criminalize almost everyone creating conditions for easy and frequent arrests – especially for warrants for failure to appear, for breaches, for minor drug offences and street disorder charges like panhandling, vending and public drunkenness.

The population of Canada’s prisons says much more about the racist and colonial nature of the Canadian society than the ‘crimes’ of the incarcerated. Indigenous people make up about 4% of the population of Canada but are more than 23% of people incarcerated in the federal system. In the Prairie provinces (Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta) Indigenous people are about 50% of the incarcerated population in the federal system, and an even higher proportion in the provincial system. The mass incarceration of Indigenous women is even more disproportionate, with Indigenous women making up about 4% of all women but 41% of all incarcerated women.

Along with Black people who make up about 2.5% of the Canadian population but over 9% of the prison population, Indigenous people account for much of the 75% increase in ‘visible minorities’ in Canadian prisons in the last decade. Each of these statistics demonstrate the continuing significance of systemic racism and colonialism in shaping the criminal justice system, and this is without including the nearly 10,000 migrants jailed in Canada in 2013 for a total of 183,928 days or 504 years.

Restructuring of social programs to maximize the control function

Under the historic welfare state, government social programs – unemployment insurance, welfare, public education, public healthcare, public transit – were developed to transfer a small portion of the socially generated surplus back to the working class. These programs served both a use function (for the working class communities that rely on them economic stability and survival) and a control function (for the ruling class who uses them to cover up the underlying system of exploitation and to tie people ideologically and materially to the current order). As part of the basic economics of neoliberalism these programs have been gutted through a mixture of privatization, contracting out, and shifting the burden of payment onto those who rely on the program (through user fees), thus undermining their redistributive function. These changes erode or eliminate the use value of social programs for working class people.

Under the neoliberal containment state, the role and purpose of social programs is further transformed. More specifically, new structures and processes are introduced exclusively to increase the control function of social programs, which become increasingly intertwined with institutions of repression.

Transit in Vancouver is a good example. In the first decade of the 21st century the regional transit authority rapidly increased fares, decreasing the redistributive function of the public service for transit dependent working class people (who are disproportionately women and people of colour). At the same time Translink created a new police service, armed with semi automatic pistols on the buses and skytrain. The role of this police force is to ticket, publicly humiliate, and in some cases violently arrest those unable to pay the fare. Translink is also paying$171 million to install fare gates in the metro stations to capture (by their own figures) about $6 million per year in unpaid fares.

Another example is welfare in B.C. The welfare rates have not risen substantially in 30 years, and are now so low that the Dieticians of Canada published a report showing that a person cannot eat properly on the current BC welfare rates, even if they were to spend their entirely monthly disposable income on food. Meanwhile the control function of welfare, mainly aimed at forcing people into any kind of exploitative low-wage work available, has increased with wait times to get on welfare, regular demands for proof of job searches, and mandatory participation in ineffective job search programs. Most relevant to emergence of the neoliberal containment state, however, is the increased securitization of interactions with welfare and the increasing direct involvement of police.

Under the new set up all requests and inquiries be made over the phone through a centralized call centre and the only face to face interaction in the remaining welfare offices is with clerical staff who accept and give out forms but don’t have any actual decision making power. These offices are routinely staffed by private security guards and all interactions take place through security glass. People on welfare no longer have an assigned social worker with whom they can develop an ongoing relationship. In interactions over the phone, ‘tone of voice’ or any degree of emotion are used by social workers to hang up and end the interaction. Thus the predictable anger of people who are being literally starved amid the conspicuous consumption and waste of Canadian capitalist society is met with ‘security’ and containment.

A further illustration is the provincial legislation enacted in June 2010 whereby people with an outstanding warrant anywhere in Canada can be denied or cut off welfare; thus the welfare state institution is transformed in such a way as to prop up and support the neoliberal containment state.

The Containment State as an Instrument of Canadian capitalism, colonization, and imperialism

Labour market management: Controlling the ‘surplus population’

Managing the labour market is a major function of bourgeois governments in a capitalist economy. This means maximizing the rate of exploitation of the working class while mitigating resistance, rebellion or disruption to capitalist accumulation.

In a monopoly capitalist economy, high rates of unemployment and underemployment are considered normal and desirable. Unemployment has an active function, operating as a downward pressure on wages and a fetter on the rate of inflation. The rich want inflation kept low because when it rises it erodes their accumulated wealth. Moreover, monopoly capitalism as a system tends not to reinvest the surplus (profit) extracted from the working class in job generating activity, instead sinking a high proportion of the surplus into socially harmful activities like advertising, speculative financial activities, real-estate and the war economy.[1] Monopoly capitalism therefore generates high rates of unemployment and, particularly in its neoliberal form, fewer and fewer stable, ‘well-paid’ jobs.

Under neoliberal capitalism the real rate of unemployment has increased substantially, especially since the ‘great recession’ of 2008-9. The official unemployment rate does not reflect the experience of millions of working class people: ‘discouraged’ workers no longer looking for work; the vast increase in contract, temporary and part time work; and most importantly those who are considered ‘unemployable’ under capitalism. The latter group are those who are not considered good candidates for extraction of surplus value and would require social supports in order to participate in social production under capitalism – people with physical differences (‘disability’), ‘mental illness,’ with addictions or with dependent family members. This is the vast pool of labour energy and talent that capitalism not only cannot absorb but actively seeks to marginalize and contain.

Under capitalism these portions of the working class are played off each other in order to keep wages down and keep workers insecure. But the large ‘surplus’ population also creates problems for capitalism. People who are too poor or hopeless, and who lose any sense of faith in or connection to the system, will eventually become rebellious.

The Welfare State had a certain way of containing discontent and the potential of militancy and rebellion among the working class:

i. Redistributive programs like unemployment insurance, public health insurance, welfare and public education paid for by a ‘progressive’ income tax regime. These programs did not challenge the basic capitalist principles of private ownership and control of the economy, operating instead through progressive taxation, where those who make more money pay a higher proportion in taxes.

ii. A relatively high union density, including business unions who play a dual function representing workers in the collective bargaining system but also disciplining workers and ensuring that they continue to play within the rules of the ‘the game.’ This role has been very evident in the period of transition where the union leadership has acted as a break on working class militancy and resistance to austerity, i.e. ‘Operation Solidarity’ in B.C. in 1983, the ‘Days of Action’ against Mike Harris in Ontario in the 1990s, and the the Hospital Employees Union strike in B.C. in 2004.

iii. The “Canadian Dream” – the promise that if you work hard your children will have opportunities for upward mobility and a better life (materially). This promise has historically been real for the white working class and farmers based on settler privilege in the colonial system and the super profits of imperialism. During the welfare state period this ‘dream’ was extended to many immigrants and refugees from non-European countries as well, although the levels of exploitation and self-sacrifice demanded from these groups was higher.

Under neoliberalism the economic basis for these containment strategies has been dismantled or evaporated:

i. Adaptation to ‘globalization’ and debt hysteria were used to justify slashing social spending and re-configure the taxation regime in favour of the rich. Redistributive programs that remain have been restructured to increase their control function while reducing their use function for working class people.

Unemployment Insurance (ideologically rebranded as ‘Employment Insurance’) is one very good example of this shift. While benefits have been cut back and made harder to access for the workers who pay into the program, the rules have been changed to force workers into whatever crappy, sub-standard jobs are available. Examples of this include changing the definition of ‘suitable employment,’ as well as new punitive and patronizing measures to ensure that unemployed workers are engaged in a ‘job search.’ Meanwhile tens of billions of dollars in surplus from the program have been rolled into general revenues, essentially comprising a new regressive tax on workers.

ii. Unionization rates have decreased significantly dropping from 38% of all workers in 1981 to 30% in 2012. Some of this is due to the shift of industrial production to the South in response to free trade agreements and liberalization of international trade. Individual capitalists also take advantage of their relative strength to bust unions or prevent them from starting altogether in order to maximize profits. While unions still play an important mediating role – especially in the remaining industrial economy and the public sector – their relative weakness is demonstrated by the willingness of governments to use legislation to send striking workers ‘back to work,’ no-strike clauses in collective agreements, and the rolling back of benefits and pension plans. Amidst shrinking union density and ineffectiveness of the unions that remain, the union bureaucracy can no longer credibly claim to represent the working class, nor sell their ability to ‘manage’ the class as a whole.

iii. Under neoliberal monopoly capitalism the “Canadian Dream” is a fantasy, even for the white working class, but especially for new immigrants and refugees. Canada’s immigration policies have always been shaped by the labour requirements of Canadian capitalism. Under welfare state capitalism there was a sense that, after a certain period of super-exploitation, immigrants or their children would eventually reap the benefits of Canadian citizenship – albeit within a profoundly racist and colonial state.[2] Under the neoliberal capitalism this ‘reward’ is no longer on offer, as exploited workers from the South are forced into a state of permanent precariousness, vulnerable to criminalization and deportation even after having ‘achieved’ citizenship. Individually these workers are super-exploited under Temporary Foreign Worker Programs, which hugely ramp up the power of capital and management. This exploitation by Canadian capital extends to whole oppressed nations because the cost of reproduction of these workers (childcare, education, health care and elder care) are born by those countries of origin, particularly by poor women in those countries. Meanwhile Canadian capitalists exploit their labour power during the period of their life when they are the most ‘productive’ in the conventional capitalist sense. Thus, it is fair to say that the record profits of Canadian banks are based in a very real way on exploiting the ‘women’s work’ of working class and peasant women of the ‘Third World.’ This dynamic, which has always existed within the patriarchal and racist framework of imperialism, is heightened in this period of neoliberalism.

The neoliberal strategy for managing monopoly capitalism has definitely eclipsed the welfare state strategy of a previous era. Today the elements of the welfare containment state dissolve, giving way to a strategy of neoliberal containment rooted in police, prisons, and criminalization. The increased capacity for the exploitation of the working class relies on the increased repressive capacity of the neoliberal containment state.

Criminalization and Mass Incarceration as a tactic of colonial control

In addition to the their national oppression under Canadian settler-colonialism large numbers of Indigenous people in Canada have historically been exploited as workers. In 19th-century British Columbia, Indigenous workers were super-exploited within a (formal) racialized labour structure in numerous industries. In the first half of the 20th Century Indigenous workers played a vital role in key ‘resource’ industries as skilled and ‘semi-skilled’ workers. Indigenous workers have also acted as special ‘reserve army of labour’ in the capitalist labour market, employed in large numbers seasonally or in times of economic boom, returning to traditional or communal economies in the offseason or in periods of economic ‘downturn.’ Under neoliberalism the ‘last hired, first fired’ integration of Indigenous people into the capitalist labour force continues, with Indigenous workers having a lower labour market participation rate and much higher rates of unemployment. Thus the numerous ways in which the neoliberal control apparatus is used to discipline and control working class people generally also applies to working class Indigenous people.

However the massive disproportionate number of Indigenous people incarcerated and cycled through the criminal justice system cannot be explained exclusively by their place within the Canadian class structure. This is especially the case when we see that historically the disproportionate incarceration of Indigenous people begins toescalate only in the 1940s – prior to that the proportion of Indigenous people incarcerated roughly reflected the proportion of Indigenous people in the population generally. To understand this change and massive disproportion in incarceration rates we have to understand the neoliberal containment state as also being linked to a new regime of colonial control.

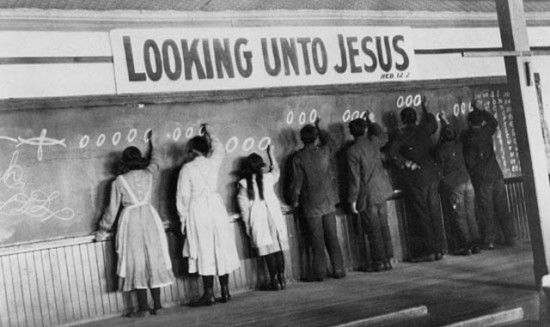

Image from residential school.

One way to understand the disproportionate incarceration of Indigenous people in Canada is as a ‘successor system’ to residential schools. Residential schools, with the stated objective to ‘kill the Indian in the child’ were a central tactic of the genocidal Canadian colonial strategy going back to at least 1874 when the federal government took up a role in financing and administering residential schools. The kidnapping, indoctrination and torture of Indigenous children in these institutions was conducted within the main Canadian colonial strategy of forced assimilation. The number of children in residential school peaked in 1931 and declined steadily until the closure of the last school in the 1990s. But during the period of decline the number of Indigenous children in ‘foster care’ began to steadily increase and beginning in the 1940s the disproportion of Indigenous people incarcerated also begins to steadily increase.

Therefore mass incarceration is referred to as a successor system to residential schools because so many Indigenous people who are incarcerated are survivors of residential school or the children and grandchildren of survivors. It is not surprising that these survivors would be concentrated in the most highly criminalized sectors of society (the homeless, extremely poor, drug users, and the chronically ill) given their experience of family and cultural disruption and social, physical and sexual abuse in residential schools.

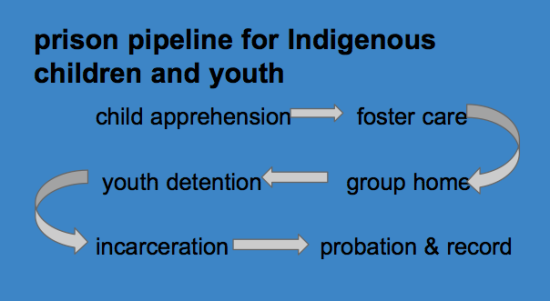

But it is not as though the mass incarceration of Indigenous people is just a colonial hangover of a previous ‘bad policy’ as many progressive-liberal narratives would have it. Mass incarceration is also a successor system because the “prison pipeline” (child apprehension –> foster care –> group home –> youth detention –> prison) has replaced residential schools as a key colonial instrument for disrupting, dividing and controlling Indigenous populations. The mass incarceration of Indigenous youth – 41% of federally incarcerated Indigenous people are under 25 years of age – is a pretty good indicator of who the Canadian state and Canadian ruling class view as the greatest danger to ‘stability’ and ‘order’ in Canada. The colonial mechanisms of child apprehension, foster care, criminalization and incarceration of youth are a highly effective disruption of Indigenous families and communities, and a barrier to youth becoming connected to their communities, history of struggle, and militant resistance to Canadian colonialism. Thus the mass incarceration of Indigenous people is a main instrument of colonial containment.[3]

A historical materialist analysis of the emergence of the neoliberal containment state

The transition from welfare state containment to the neoliberal containment state has been described as capitalism switching from it’s left hand to it’s right. This description is apt in the sense that the same basic mechanisms of capitalist exploitation endure, based on racist colonial domination, and on the patriarchal super-exploitation of women, especially women’s reproductive labour.

However, it is inaccurate in the sense that Capitalism cannot easily switch back and forth between regimes of containment. These regimes are historically shaped by underlying economic, political and ideological factors. The neoliberal containment state adapts existing state institutions and practices to better support and perpetuate the economic and political superstructures of neoliberalism.

Looking at the the 30-year development of the neoliberal project in Canada it becomes evident that the dismantling of the monopoly capitalist welfare state in Canada and its replacement with monopoly capitalist neoliberal state has been carried out by successive governments with different leaders and members and under different political labels:

1984 – 1993, Progressive Conservative Party (PMs Brian Mulroney & Kim Campbell): free trade agreements – liberalization of international trade in the interest of capitalists; privatization (Air Canada/ Petro Canada); beginnings of debt hysteria and austerity;

1993 – 2006, Liberal Party (PMs Chretien and Martin): debt panic; austerity – dismantling of redistributive and social wage programs; restructuring of tax regime;

2006 – Present, Conservative Party (PM Harper): neoliberal containment state; restructuring of immigration policy to increase exploitation of immigrant workers from the Third World; aggressive development of extractive industries (oil, gas); militarization of foreign policy.

To whatever extent there was a debate within the ruling class class about whether Canadian capitalism would adopt a neoliberal economic framework it would have been during the ‘great free trade debate’ of the 1988 election and was decided decisively in favour of neoliberalism.

To understand the ideological roots of neoliberalism – not it’s intellectual roots, but the historical factors shaping the outlook and worldview of the ruling class – we have to go back farther and look at the actual class experiences of the ruling class that generated the welfare state, versus those of the ruling class who generated the neoliberal state. The great historical events of the 20th century – inter-imperialist war; the Russian Revolution and the wave of working class militancy and rebellion that followed it; the collapse of the global capitalist economy and the failure of fascism as a reliable option for capitalist rule -– had a profound ideological impact on all classes. For the capitalist ruling class in particular these experiences undoubtedly created a fertile ground for the ideas of Keynesianism and an approach to managing capitalism that could mitigate some of the most destabilizing and potentially explosive class contradictions. On the other hand the ruling class that gave rise to neoliberalism has a very different class experience: U.S. hegemony; the postwar economic boom; division and weakness of the International Communist Movement; and the success of State sponsored anti-communism.

| Welfare State (1940s to 70s) | Neoliberal State (1980s to now) | |

| Containment regime | Business unionism, social democracy & Canadian “left” nationalism/ public education/ official anti-communism | Police, prisons & security/ market fundamentalism/ individualism / “anti-terrorism” |