by Ellie Adekur-Carlson

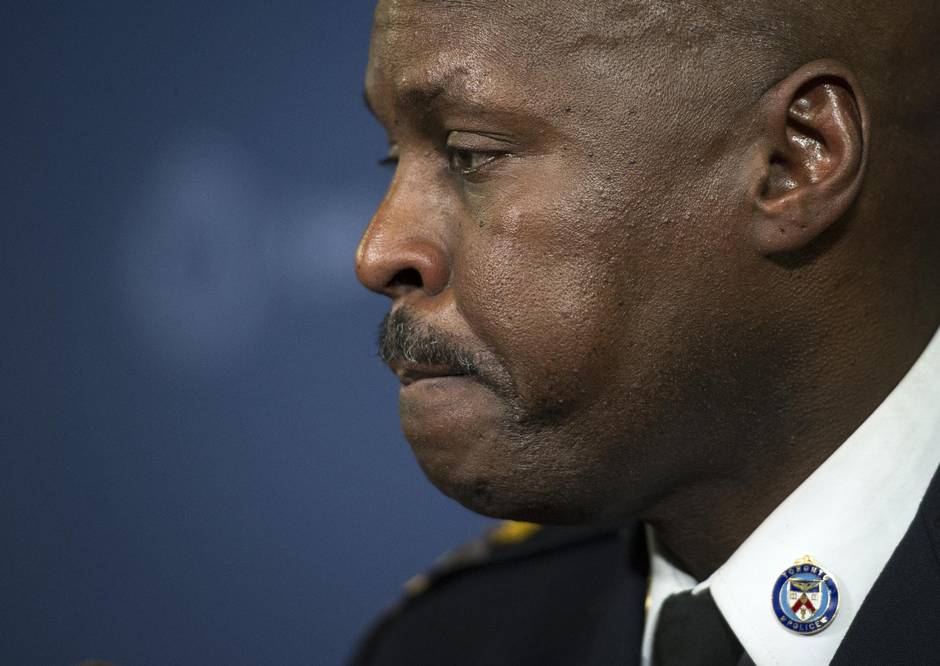

When Mark Saunders and Peter Sloly were shortlisted as candidates for Chief Bill Blair’s job, it struck up a city-wide dialogue around diversity and the role of a Black police chief in tackling issues of anti-Black racism within the Toronto Police Service. Communities were proud to watch, for the first time, as men of colour rose through the ranks of the TPS, and when Mark Saunders was sworn-in, excited to begin unpacking issues of racial profiling and police violence in our city.

Mark Saunders is a Black face in a traditionally white space, but the celebration is cut short when his approach to policing upholds many of the same campaigns that disproportionately target and oppress communities of colour. Saunders has been part (and too often in charge) of divisions within the police service that, historically and currently, target and harass young men and women of colour, and instil in us a sense of fear when we think about policing.

What we are now learning is that putting a Black man in charge is not enough to meaningfully combat anti-Black racism. Saunders’ Blackness is a symbolic victory for diversity, but it doesn’t translate into tangible gains for communities of colour across the city; his swearing-in was not followed by meaningful policy change, nor even an acknowledgement of anti-Black racism in carding policies that, to date, have logged more encounters with young Black men than the actual population of young Black men in Toronto. For this reason, the conversation isn’t and cannot be about diversity within the TPS. We need a larger discussion around racism, classism and the adversarial relationship between the TPS and working-class communities in Toronto.

Carding—a practice that parallels the stop-and-frisk mandate of the NYPD—is a pre-emptive policing strategy that looks to tackle crime before it occurs in communities through indiscriminate, unwarranted contact with residents. The practice is loaded with issues of race- and class-based profiling. We now know that certain kinds of people in the city of Toronto are systematically stopped under these policies. Young men and women of colour are stopped and interrogated, with intimate details about our lives documented and logged in an expansive database. These encounters are deceptive, intimidating, and often degrading—creating a feeling that you can’t say “no”, because the police have guns and are largely unaccountable to anyone for the injuries they inflict.

When you’re carded, officers rarely inform you of your right to leave and demand intimate details about you, your intentions, and your background. When you hesitate, or refuse to give this information, officers bend the law to obtain it, threatening charges of trespassing, loitering, or officer baiting. Too often they resort to physical violence to get it, understanding that the complaint process is an inaccessible one, and that even when civilians do file complaints related to officer misconduct, rarely is the officer disciplined for this kind of violence.*

Carding is a very real example of how public encounters with the Toronto Police Service create a culture of fear around policing which runs so deep that many of our community partners refuse to call the police even when they are in serious danger. From an early age many Torontonians learn that the police are not their friends, and that officers are not stationed in schools, at community centres, and on their streets to serve and protect them.

Instead, many young people growing up in Toronto’s priority neighborhoods learn to actively avoid officers because of widespread harassment. Youth with precarious status learn that their in-school resource officers work closely with Canadian Border Services to police families without status. Because of the relationships that the Toronto Police Service has with agencies like the CBSA, the Toronto District School Board and Toronto Community Housing, negative interactions with police can have severe consequences – deportation, expulsion and eviction. For these reasons, we see people in this city, right now—entire communities—establishing their own systems of policing to avoid this one.

TPS has moved beyond policing as a tool for crime prevention and instead uses it as a regulatory tool that isolates, targets, and oppresses Toronto’s most marginalized communities. The trajectory of policing in our city has much more to do with the social and economic makeup of Toronto and in our city we criminalize poverty—we fine poverty and toss it in holding cells for sleeping on park benches (trespassing, loitering) and begging for money (harassment). The Toronto Police Service cites crime reduction as justification enough for these policing strategies, but we see too often that these mandates are used as a guise to control “problem areas” and “problem people”.

We’re operating on a punitive model of justice that looks to punish deviance and criminalize things like poverty, mental health, addictions, and homelessness. Our police reflect a larger correctional system that looks to solve issues of crime through punishment, without thinking about rehabilitative alternatives. This kind of correctional orientation translates into the kind of brutal “community policing” initiatives that alienate a certain subset of our city—young men and women of colour, poor and marginally housed Torontonians, those with mental health and addictions related issues, sex workers, and people with precarious status.

We don’t need police half as badly as we need affordable housing, shelter, basic income, access to proper care, and opportunity. We have the capacity to build safe and healthy communities by breaking down the TPS’ billion-dollar budget and pouring these resources into development and restorative justice at the grassroots level. A lot of this discussion comes down to what we believe justice is. If our legal framework is built on punishment, it is built to oppress—to isolate the wrongdoer and punish them.

So is justice punishment? Or is justice a transformative experience, something that looks to heal communities? When we concentrate on restorative justice, we look to transform communities and transform people. This is something that’s already happening at the community level in Toronto as a response to particularly punitive policing strategies in Rexdale and Jane & Finch. Under its current framework, the Toronto Police Service operates as a billion-dollar gang and Chief Saunders as a face-lift that brings no real change.

The most powerful and effective alternatives to policing—community patrols in the downtown eastside, sex workers coordinating and organizing safe business models, and restorative justice networks across the GTA—have all grown out of a need for marginalized communities to protect themselves from violence, from harm, and from those who claim to serve and protect the rest of Toronto.

*The ultimate guarantor of violent police misconduct is the Special Investigations Unit. The SIU is a civilian oversight body that employs both civilians and former officers to conduct independent investigations in cases where a civilian has been seriously injured by an officer. Between 1990 and 2010, the SIU conducted 3,400 independent investigations, filing criminal charges in 95 of these cases. Of that, 16 officers have been convicted of a crime and 3 spent time in prison.

(Photo Credit: Kevin Van Paassen/The Globe and Mail)

Comments